William Wroth: The Apostle of Wales

NOTE BEFORE READING: references are indicated by bold numbers in brackets [1] and footnoted at the bottom of the article. The list of sources follow. All photographs are my own.

On the right, about two miles west of Caerwent in Monmouthshire, along the A48, stands Tabernacle Chapel, on the outskirts of Llanfaches. It is a memorial chapel built in 1803 and remodelled sometime during the last century. It closed its doors for the final time in December 2025.

The church itself began in 1639 by a man called William Wroth. It was the first Independent (nonconformist) church in all of Wales which means it was the first church not to be Roman Catholic or part of the Church of England.

The original chapel was not situated at the current site but in the nearby hamlet of Carrow Hill. The precise location is unknown, but a cottage there bears Wroth’s name which was probably his dwelling place. The chapel would have been somewhere nearby. Local rumour says a previous owner of this cottage found the foundations of an old building, possibly a church, in the garden while he was digging one day. Could it be the original building? We will never know the exact location. It is lost to history. But that doesn’t matter. What matters it how the church began.

The church itself began in 1639 by a man called William Wroth. It was the first Independent (nonconformist) church in all of Wales which means it was the first church not to be Roman Catholic or part of the Church of England.

The original chapel was not situated at the current site but in the nearby hamlet of Carrow Hill. The precise location is unknown, but a cottage there bears Wroth’s name which was probably his dwelling place. The chapel would have been somewhere nearby. Local rumour says a previous owner of this cottage found the foundations of an old building, possibly a church, in the garden while he was digging one day. Could it be the original building? We will never know the exact location. It is lost to history. But that doesn’t matter. What matters it how the church began.

Tabernacle Chapel, Llanfaches.

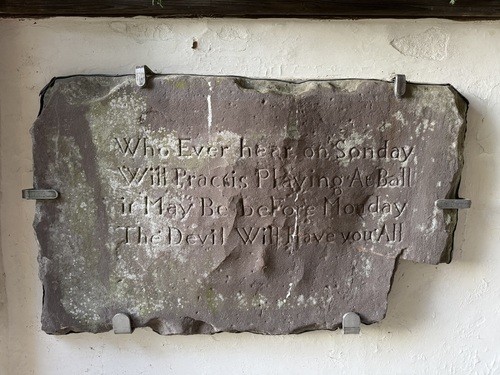

The memorial plaque at Tabernacle Chapel, Llanfaches.

The Apostle of Wales

Wroth is arguably one of the most important historical figures in Welsh nonconformity, yet he is not well known today. He became known as the Apostle of Wales and the father of Welsh Puritanism. At the height of his ministry he attracted hundreds, if not thousands, of listeners to Llanfaches.

Many prominent Welsh Puritans went to learn from him, including Walter Cradock, Vavasor Powell, and the famous poet Morgan Llwyd, who was converted under Cradock’s ministry and followed him to Llanfaches to be part of the new puritan church for a while.[1] After Wroth’s death, Cradock seems to have taken over from him at the new independent church at Llanfaches for a while.[2] Powell’s ministry extended across the counties of Montgomeryshire and Radnorshire and part of Breckonshire.[3] Llwyd later became a chaplain in Oliver Cromwell’s army during the English Civil War before becoming a minister and an accomplished poet.[4] Powell and Llwyd could be considered sons in the faith to Walter Cradock.[5]

Many prominent Welsh Puritans went to learn from him, including Walter Cradock, Vavasor Powell, and the famous poet Morgan Llwyd, who was converted under Cradock’s ministry and followed him to Llanfaches to be part of the new puritan church for a while.[1] After Wroth’s death, Cradock seems to have taken over from him at the new independent church at Llanfaches for a while.[2] Powell’s ministry extended across the counties of Montgomeryshire and Radnorshire and part of Breckonshire.[3] Llwyd later became a chaplain in Oliver Cromwell’s army during the English Civil War before becoming a minister and an accomplished poet.[4] Powell and Llwyd could be considered sons in the faith to Walter Cradock.[5]

Early Life and Education

Wroth was likely born around 1576 into an aristocratic family near Abergavenny. He was educated locally before leaving Wales for Oxford at just fourteen where he spent fifteen years, graduating with a B.A. from Christ Church and an M.A. from Jesus College. He returned to Wales and lived for a time with Sir Edward Lewis at the Fan, Caerphilly, who promised him the rectory of Rogiet in 1613 and later at Llanfaches in 1617 when it became vacant. He ministered at both places until he had a spiritual experience in 1626, which led him to resign from Rogiet and focus solely on Llanfaches.[6]

Unconverted Yet Ordained

Even though Wroth was a rector in the Church of England, like many of the clergy, he was unconverted. By this I mean that his religion was not shaped by personal faith or deep conviction, but was largely a matter of performing religious duties simply because they were required of him. He may have desired to be pious, yet he had not known Jesus as his Saviour. Remarkably, his conversion came while he was already ordained. Isn’t that strange?

Like many of the clergy, he had little care for the gospel—the good news of saving faith—which is at the heart of Christianity, and probably had no understanding of the gospel or key doctrines such as Justification by Grace through Faith Alone which was at the heart of the Reformation just a century earlier. Learning that salvation is a gift from God, not earned through good works, would not only save him but also transform him into one of the most powerful preachers in all of Wales.

Like many of the clergy, he had little care for the gospel—the good news of saving faith—which is at the heart of Christianity, and probably had no understanding of the gospel or key doctrines such as Justification by Grace through Faith Alone which was at the heart of the Reformation just a century earlier. Learning that salvation is a gift from God, not earned through good works, would not only save him but also transform him into one of the most powerful preachers in all of Wales.

Conversion

A keen musician and skilled on the harp (a true Welshman), prior to his conversion he would play it in the churchyard after the morning service as a way to entice the locals to attend the evening service.[7] But soon, it would be his preaching and passion for the gospel, not the harp, that eventually brought listeners.

His conversion marked a dramatic turning point in his life, though accounts differ in detail. It appears to have occurred around 1625-1626, when the head of the household where he lodged, having just won a legal case, planned a celebration at which Wroth would provide the music. But before the man could return home, he died. The shock of this struck Wroth terribly that he threw away the harp and fell on his knees in the midst of all and prayed.[8]

This sudden realisation of life’s fragility and the seriousness of eternity turned his heart toward God. There are two accounts of Wroth’s conversion mentioned in R. Geraint Gruffydd’s work, In That Gentile Country. The first account is by Thomas Charles who published it in Trysorfa Ysprydol and the other is by the baptist historian Joshua Thomas[9] which “is less full and differs in detail, but also has some additional material”.[10] Charles gives the following account:

He learned to play upon the harp, and before his conversion would play upon it in the churchyard to divert people in the evening of the Lord’s Day after the morning service. Thus Mr. Wroth spent the Lord’s Day in his unconverted state until the mercy of God intended for him began to operate toward him in the following manner. The master of the family where he lodged and to whom he himself was related, having bought a new harp for him in London, came down to Colebrook on his way home, fell sick there and died. Notice was sent to the family, but before they went he had been buried. This great and sudden turn of providence greatly affected him, and put him on thinking of the world to come. This was greatly helped on by an extraordinary dream he had at that time. He dreamed he was in a great flood in danger of drowning, in great fear, apprehending him he was quite unfit to die. While in this perplexity he saw in his dream standing on the bank of the river a beautiful young man with a sky coloured cap or crown on his head. He said to him, ‘What wilt thou do to have thy life saved?’ He answered, ‘I will do anything to have my life.’ Then replied the other, ‘Make restoration, and go and preach the Gospel.’ When he awakened he was greatly affected and resolved to obey. Accordingly he sent for one to whom he had lent money on interest and returned so much back that he impoverished himself; and studied a sermon to preach without telling the people of it, not knowing how he should come off. For before he had only read the Common Prayer to a few old people and those hard by, for the young people met in the afternoon to play in the churchyard, who expected him to come among them with his harp, and wondered he did not come, but were told by those that had heard him that he had preached a sermon, which brought more to the church the next Lord’s Day, and the next Lord’s Day more, and the whole parish and about, still increasing more and more, so Llanfaches church was another sort of place from what it had been before. The congregation increased continually, so that the church became much too little, and Mr. Wroth was obliged to come out to the churchyard, which had been before profaned, though called consecrated ground, was indeed [consecrated], by the presence of God and the preaching of the Gospel, whereby many sinners were turned from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to the living God.[11]

Wroth was transformed, and so was his ministry. He abandoned his former lighthearted approach to life and ministry and embraced a gospel-centred calling. Within less than a decade, he became the leading Puritan in Wales.

But how?

His conversion marked a dramatic turning point in his life, though accounts differ in detail. It appears to have occurred around 1625-1626, when the head of the household where he lodged, having just won a legal case, planned a celebration at which Wroth would provide the music. But before the man could return home, he died. The shock of this struck Wroth terribly that he threw away the harp and fell on his knees in the midst of all and prayed.[8]

This sudden realisation of life’s fragility and the seriousness of eternity turned his heart toward God. There are two accounts of Wroth’s conversion mentioned in R. Geraint Gruffydd’s work, In That Gentile Country. The first account is by Thomas Charles who published it in Trysorfa Ysprydol and the other is by the baptist historian Joshua Thomas[9] which “is less full and differs in detail, but also has some additional material”.[10] Charles gives the following account:

He learned to play upon the harp, and before his conversion would play upon it in the churchyard to divert people in the evening of the Lord’s Day after the morning service. Thus Mr. Wroth spent the Lord’s Day in his unconverted state until the mercy of God intended for him began to operate toward him in the following manner. The master of the family where he lodged and to whom he himself was related, having bought a new harp for him in London, came down to Colebrook on his way home, fell sick there and died. Notice was sent to the family, but before they went he had been buried. This great and sudden turn of providence greatly affected him, and put him on thinking of the world to come. This was greatly helped on by an extraordinary dream he had at that time. He dreamed he was in a great flood in danger of drowning, in great fear, apprehending him he was quite unfit to die. While in this perplexity he saw in his dream standing on the bank of the river a beautiful young man with a sky coloured cap or crown on his head. He said to him, ‘What wilt thou do to have thy life saved?’ He answered, ‘I will do anything to have my life.’ Then replied the other, ‘Make restoration, and go and preach the Gospel.’ When he awakened he was greatly affected and resolved to obey. Accordingly he sent for one to whom he had lent money on interest and returned so much back that he impoverished himself; and studied a sermon to preach without telling the people of it, not knowing how he should come off. For before he had only read the Common Prayer to a few old people and those hard by, for the young people met in the afternoon to play in the churchyard, who expected him to come among them with his harp, and wondered he did not come, but were told by those that had heard him that he had preached a sermon, which brought more to the church the next Lord’s Day, and the next Lord’s Day more, and the whole parish and about, still increasing more and more, so Llanfaches church was another sort of place from what it had been before. The congregation increased continually, so that the church became much too little, and Mr. Wroth was obliged to come out to the churchyard, which had been before profaned, though called consecrated ground, was indeed [consecrated], by the presence of God and the preaching of the Gospel, whereby many sinners were turned from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to the living God.[11]

Wroth was transformed, and so was his ministry. He abandoned his former lighthearted approach to life and ministry and embraced a gospel-centred calling. Within less than a decade, he became the leading Puritan in Wales.

But how?

Growth and Opposition

After his conversion, Wroth resigned from the church at Rogiet and focussed on Llanfaches. His preaching was simple but powerful, and his church thrived because of it. He drew crowds from all around. Crowds as far as Somerset, Gloucestershire, Bristol, Herefordshire, Radnor and Glamorganshire came to hear him preach. As we have already seen from Charles’ account of his conversion, so many attended that he often had to preach in the churchyard.[12]

But with the growth of his ministry, opposition also increased. In 1633, King Charles I and Archbishop William Laud republished the Declaration of Sports (or Book of Sports), a pamphlet which had to be read aloud in every church outlining the additional sports and recreations which were permitted to take place on Sundays.[13] It was an antagonistic move on the their part who sought to counteract the Puritanical teaching.

Wroth took a great offence to this since it discouraged people from worshipping God by prioritising recreational activities above the importance of worship. To him, Sunday (the Lord’s Day) was a divine gift, not a cultural habit. At the risk of excommunication, he refused to read it.

But with the growth of his ministry, opposition also increased. In 1633, King Charles I and Archbishop William Laud republished the Declaration of Sports (or Book of Sports), a pamphlet which had to be read aloud in every church outlining the additional sports and recreations which were permitted to take place on Sundays.[13] It was an antagonistic move on the their part who sought to counteract the Puritanical teaching.

Wroth took a great offence to this since it discouraged people from worshipping God by prioritising recreational activities above the importance of worship. To him, Sunday (the Lord’s Day) was a divine gift, not a cultural habit. At the risk of excommunication, he refused to read it.

St. Dyfrig (Dubritius’) Church, Llanfaches

Two different stiles at St. Dyfrig’s Church, Llanfaches

A Different World

The world in which Wroth lived was very different to ours today. It is now very normal to play sports on a Sunday instead of attending church. Before rushing to make judgements about Wroth as some overly religious spoilsport, we need to understand his world and the state of the church to make sense of why he would take such a strong stance against the Book of Sports which to many today would be seen as harmless.

The issue was never really about sport. The question beneath it all was who had the right to shape the worship and conscience of the church; Christ or the crown? The Archbishop and the King were not simply encouraging people to relax after church. They were deliberately using political power to weaken Puritan influence and to redefine the meaning of the Lord’s Day—the appointed day for Sunday worship. Many saw this as a challenge to the authority of God over the life of His people.

The Lord’s Day was not seen a cultural habit, but a divine gift that should be honoured. Almost everyone went to church in those days. It was a weekly reminder that life did not revolve around the labour and toil of work, but around the worship of God in community. Rest should be found in Christ and the gospel, not in recreational activities.

To publicly promote sport and recreation on that day was to slowly shift the heart of the community away from worship and toward self-gratification. This is why Wroth refused to read the declaration, even at the risk of his livelihood. He knew that once the church surrendered its conscience to the state in small matters, it would soon surrender it in greater ones.

In 1642, just a few years after the Declaration of Sports was reissued, the English Civil War broke out across Great Britain and Ireland between the Royalists and the Parliamentarians—an ugly war intermixed with politics and religion. The kind of antagonism caused by the Book of Sports played into the build-up toward the English Civil War. It was not the sole cause, but certainly a piece of a much larger picture. Wroth would not live to see the English Civil War, but many of his followers did.

The issue was never really about sport. The question beneath it all was who had the right to shape the worship and conscience of the church; Christ or the crown? The Archbishop and the King were not simply encouraging people to relax after church. They were deliberately using political power to weaken Puritan influence and to redefine the meaning of the Lord’s Day—the appointed day for Sunday worship. Many saw this as a challenge to the authority of God over the life of His people.

The Lord’s Day was not seen a cultural habit, but a divine gift that should be honoured. Almost everyone went to church in those days. It was a weekly reminder that life did not revolve around the labour and toil of work, but around the worship of God in community. Rest should be found in Christ and the gospel, not in recreational activities.

To publicly promote sport and recreation on that day was to slowly shift the heart of the community away from worship and toward self-gratification. This is why Wroth refused to read the declaration, even at the risk of his livelihood. He knew that once the church surrendered its conscience to the state in small matters, it would soon surrender it in greater ones.

In 1642, just a few years after the Declaration of Sports was reissued, the English Civil War broke out across Great Britain and Ireland between the Royalists and the Parliamentarians—an ugly war intermixed with politics and religion. The kind of antagonism caused by the Book of Sports played into the build-up toward the English Civil War. It was not the sole cause, but certainly a piece of a much larger picture. Wroth would not live to see the English Civil War, but many of his followers did.

Wroth on Trial

Wroth’s refusal to read the Book of Sports, together with news of his open-air preaching and Puritanical teaching led Bishop William Murray of Llandaff to bring him before the High Commission Court in 1635.[14] Wroth had preached faithfully and successfully in the years since his conversion and drew large crowds. Not only did people flock to hear him, but Wroth had also become a leader of men. Two men; William Erbury, Vicar of St. Mary’s and Walter Cradock, his Curate, who was mentioned earlier, were notable Wrothian disciples. Cradock “being a bold ignorant young fellow”[15] was dismissed while Wroth and Erbury were brought before the High Commission Court and asked to account for their behaviour.

For three years no verdict was reached, allowing their ministry to continue until 1638, when the court demanded that the men must conform. Wroth replied to the Bishop, “with tears, there are thousands of immortal souls around me thronging to perdition, and should I not use all means likely to succeed to save them?”[16] According to Thomas Charles, the Bishop, worried for his own position admitted, “I shall lose my place for your sake”.[17] Wroth surprisingly conformed to the court, though Erbury resigned.

For three years no verdict was reached, allowing their ministry to continue until 1638, when the court demanded that the men must conform. Wroth replied to the Bishop, “with tears, there are thousands of immortal souls around me thronging to perdition, and should I not use all means likely to succeed to save them?”[16] According to Thomas Charles, the Bishop, worried for his own position admitted, “I shall lose my place for your sake”.[17] Wroth surprisingly conformed to the court, though Erbury resigned.

The Warning at the Stile

Even though Wroth conformed, it did not stop him from further reforms within his church. His reluctant conformity did not mean compromise, but a strategic step in continuing his ministry. It was during this time that he engraved the following words into the large stone stile at his church in Llanfaches:

Who Ever hear on Sonday

Will Practis Playing at Ball

It May be before Monday

The Devil Will Have you All

Will Practis Playing at Ball

It May be before Monday

The Devil Will Have you All

What a strong warning! In order to enter a churchyard in those days, one had to step over a waist-high stile made of a large flat stone which prevented livestock from grazing on the cemeteries. Two stiles still exist at the church today (see photographs above). It would be very difficult to enter the church without noticing this most obvious warning. This actual stile has been preserved and can be seen hanging on the wall in the porch of St. Mary’s Church, Llanfair-Discoed (see photograph below). Despite Wroth’s conformity, his warning demonstrates his insistence that God’s command for holy rest could not be ignored. According to Wroth, the spiritual implications of such ignorance would be devastating.

The engraved stile and St. Mary’s Church, Llanfair Discoed

St. Mary’s Church, Llanfair Discoed

The Birth of the First Independent Church in Wales

A year later, in November 1639, Wroth invited Henry Jessey to Llanfaches. He was a minister of a Congregational church in London who had obvious influence on Wroth and Cradock. As a result of his influence, the first Independent Church in Wales was formed, who gathered in a Church Covenant, “under which they would appoint their own officers” apart from the Church of England.[18]

Wroth became the father of Welsh nonconformity and became known as the Apostle of Wales, and Llanfaches the Antioch of Wales. Edward Whiston, the biographer of Henry Jessey, in describing Jessey’s journey to Wales, says:

“in November 1639, he [Henry Jessey] was sent into Wales by the congregation for the assisting of old Mr. Wroth, Mr. Cradock and others in their gathering and constituting the Church in Llanfaches in Monmouthshire in South Wales, which afterwards was like Antioch the Mother Church in that Gentile Country.”[19]

This new Independent church was patterned after the Congregational example of John Cotton, a Puritan leader in New England, U.S.A.[20] The first meeting took place in November 1639,[21] and Wroth died in early 1641. He is buried at the parish church of Llanfaches, known today as St Dyfrig’s (Dubritius’) Church. This Puritan movement was more than a local experiment; it became the foundation for a Puritan network across Wales; Wroth in the South and Oliver Thomas in the North.[22]

Wroth became the father of Welsh nonconformity and became known as the Apostle of Wales, and Llanfaches the Antioch of Wales. Edward Whiston, the biographer of Henry Jessey, in describing Jessey’s journey to Wales, says:

“in November 1639, he [Henry Jessey] was sent into Wales by the congregation for the assisting of old Mr. Wroth, Mr. Cradock and others in their gathering and constituting the Church in Llanfaches in Monmouthshire in South Wales, which afterwards was like Antioch the Mother Church in that Gentile Country.”[19]

This new Independent church was patterned after the Congregational example of John Cotton, a Puritan leader in New England, U.S.A.[20] The first meeting took place in November 1639,[21] and Wroth died in early 1641. He is buried at the parish church of Llanfaches, known today as St Dyfrig’s (Dubritius’) Church. This Puritan movement was more than a local experiment; it became the foundation for a Puritan network across Wales; Wroth in the South and Oliver Thomas in the North.[22]

Lessons for the Modern Church

William Wroth stands as a powerful example to the modern church and to pastors in particular, especially those concerned with theological faithfulness. His life illustrates what genuine faithfulness and fruitfulness in ministry look like. Here are three ways how Wroth‘s example remains deeply relevant to us today:

1. A pastor must be a true convert who preaches the Bible faithfully

If you attend a church and the minister does not faithfully preach and teach the Bible, then you need to stop going there because you are not listening to God. You are listening to a human being and his or her opinion. A minister’s authority comes from God’s Word, not their own ideas.

Ask yourself this: Has your minister truly encountered God? If they have never acknowledged their sin, confessed it, and received forgiveness from God, then they are still “dead in [their] trespasses and sins” (Ephesians 2:1). A minister who denies their own need for salvation has nothing to offer you.

Faithfulness also requires a correct understanding of who Christ is. If a minister denies that Jesus is both God and Man, the gospel they preach is absolutely false. Without Christ’s divinity, He cannot be our perfect substitutionary sacrifice. Without his humanity, He could not die for us and be punished in our place. More than that, if He did not rise from the dead, we have no hope.

There are many other non-negotiables—particularly core doctrines—that a church must uphold in order to experience genuine spiritual growth and the blessings of knowing Christ as Lord and Saviour. These particulars, however, are beyond the scope of this article. At the very core has to be the centrality of Christ and the gospel in accordance with Scripture.

Churches are shrinking and closing up and down the country because the gospel has been neglected and no one is being introduced to God as He is revealed in the Scriptures. Ministers who are unconverted or lukewarm lead people astray. William Wroth, in contrast, loved Jesus passionately and proclaimed the truth of the gospel without compromise. His ministry bore fruit because it was anchored in the authority of God’s Word and the reality of his own conversion. His life reminds us that church health depends not on programs, popularity, or talent, but on Christ-centred preaching and teaching by men who have encountered Christ and the gospel.

2. Growth comes from faithfulness to God’s Word

Churches cannot grow spiritually through gimmicks or entertainment. A cool band might draw a crowd, but it becomes a concert hall, not a hospital for sinners. I read last year of a church in England who was putting on silent discos to try and draw crowds. I’m up to trying out a silent disco, it sounds fun, but why would I go to a church to do that with the local vicar? That doesn’t grow a church. I have heard of churches doing the most bizarre experiments such as having pet services, “wine and wisdom” evenings, or even escape room-style Bible events. None of these things will bring spiritual growth. These are things that should take place in a village hall, not a church. They are desperate attempts to create a community because they have already lost the gospel and the supremacy of Christ. Wroth himself used to play the harp in the cemetery hoping it would attract a crowd Until he encountered Christ and the gospel.

Transformation comes when people see their sin and the impending judgement—that they are not who we should be. We are wretched sinners in need of a Saviour. Transformation comes when people repent, and turn to Christ for forgiveness and salvation.

Many prefer a “feel-good” Christianity: a church that has a minister who never mentions sin but tells nice short stories, gives moral lessons, or vague assurances that God loves you for who you are. But the only way we can really know why and how He loves us is if we grasp the fact that we are sinners who are undeserving of His love. The fact that Jesus chose to bear our judgement gives meaning to the statement “God loves you.” He loves us to death. Literally. Without the sacrifice of Christ, we would all remain under judgement. Without the resurrection, we would have no hope.

The church grows when people are confronted by the truth of their sinfulness and offered the gospel of Christ by the grace of God. When people begin to rejoice in God for who He is and what He has done, they begin to respond in obedience and serve the church and the community. We are seeing this happening at our own church. Growth flows from faithful Bible preaching, empowered by the Holy Spirit. Wroth’s church flourished because he proclaimed the gospel boldly, calling people to genuine repentance and faith in Christ.

3. Pastors must be willing to die for their convictions

Every disciple of Jesus, except John who was exiled on an island, was martyred for proclaiming the gospel. They had seen the risen Christ and could not stop proclaiming Him as the Saviour of the world.

Wroth didn’t die for his convictions, but I have no doubt that he would have. He demonstrated courage in his own life by risking his livelihood and position to follow Christ faithfully. You might think his refusal to read the Book of Sports was petty or trivial, but he didn’t think so. He was convinced that the Church of England was straying from Scripture and governed by unconverted men. Because of this he seceded from the established church and suffered opposition with unwavering faith until his death. He is the unsung hero of Welsh nonconformity. His courage reminds us that ministry is not about popularity or comfort. It is about faithfulness to Christ, and fruitfulness as a result, even when it costs everything.

In a world that often prizes ease and acceptance, Wroth challenges all Christians and ministers, that faithfulness to God may cost everything, but it is worth infinitely more than worldly approval.

1. A pastor must be a true convert who preaches the Bible faithfully

If you attend a church and the minister does not faithfully preach and teach the Bible, then you need to stop going there because you are not listening to God. You are listening to a human being and his or her opinion. A minister’s authority comes from God’s Word, not their own ideas.

Ask yourself this: Has your minister truly encountered God? If they have never acknowledged their sin, confessed it, and received forgiveness from God, then they are still “dead in [their] trespasses and sins” (Ephesians 2:1). A minister who denies their own need for salvation has nothing to offer you.

Faithfulness also requires a correct understanding of who Christ is. If a minister denies that Jesus is both God and Man, the gospel they preach is absolutely false. Without Christ’s divinity, He cannot be our perfect substitutionary sacrifice. Without his humanity, He could not die for us and be punished in our place. More than that, if He did not rise from the dead, we have no hope.

There are many other non-negotiables—particularly core doctrines—that a church must uphold in order to experience genuine spiritual growth and the blessings of knowing Christ as Lord and Saviour. These particulars, however, are beyond the scope of this article. At the very core has to be the centrality of Christ and the gospel in accordance with Scripture.

Churches are shrinking and closing up and down the country because the gospel has been neglected and no one is being introduced to God as He is revealed in the Scriptures. Ministers who are unconverted or lukewarm lead people astray. William Wroth, in contrast, loved Jesus passionately and proclaimed the truth of the gospel without compromise. His ministry bore fruit because it was anchored in the authority of God’s Word and the reality of his own conversion. His life reminds us that church health depends not on programs, popularity, or talent, but on Christ-centred preaching and teaching by men who have encountered Christ and the gospel.

2. Growth comes from faithfulness to God’s Word

Churches cannot grow spiritually through gimmicks or entertainment. A cool band might draw a crowd, but it becomes a concert hall, not a hospital for sinners. I read last year of a church in England who was putting on silent discos to try and draw crowds. I’m up to trying out a silent disco, it sounds fun, but why would I go to a church to do that with the local vicar? That doesn’t grow a church. I have heard of churches doing the most bizarre experiments such as having pet services, “wine and wisdom” evenings, or even escape room-style Bible events. None of these things will bring spiritual growth. These are things that should take place in a village hall, not a church. They are desperate attempts to create a community because they have already lost the gospel and the supremacy of Christ. Wroth himself used to play the harp in the cemetery hoping it would attract a crowd Until he encountered Christ and the gospel.

Transformation comes when people see their sin and the impending judgement—that they are not who we should be. We are wretched sinners in need of a Saviour. Transformation comes when people repent, and turn to Christ for forgiveness and salvation.

Many prefer a “feel-good” Christianity: a church that has a minister who never mentions sin but tells nice short stories, gives moral lessons, or vague assurances that God loves you for who you are. But the only way we can really know why and how He loves us is if we grasp the fact that we are sinners who are undeserving of His love. The fact that Jesus chose to bear our judgement gives meaning to the statement “God loves you.” He loves us to death. Literally. Without the sacrifice of Christ, we would all remain under judgement. Without the resurrection, we would have no hope.

The church grows when people are confronted by the truth of their sinfulness and offered the gospel of Christ by the grace of God. When people begin to rejoice in God for who He is and what He has done, they begin to respond in obedience and serve the church and the community. We are seeing this happening at our own church. Growth flows from faithful Bible preaching, empowered by the Holy Spirit. Wroth’s church flourished because he proclaimed the gospel boldly, calling people to genuine repentance and faith in Christ.

3. Pastors must be willing to die for their convictions

Every disciple of Jesus, except John who was exiled on an island, was martyred for proclaiming the gospel. They had seen the risen Christ and could not stop proclaiming Him as the Saviour of the world.

Wroth didn’t die for his convictions, but I have no doubt that he would have. He demonstrated courage in his own life by risking his livelihood and position to follow Christ faithfully. You might think his refusal to read the Book of Sports was petty or trivial, but he didn’t think so. He was convinced that the Church of England was straying from Scripture and governed by unconverted men. Because of this he seceded from the established church and suffered opposition with unwavering faith until his death. He is the unsung hero of Welsh nonconformity. His courage reminds us that ministry is not about popularity or comfort. It is about faithfulness to Christ, and fruitfulness as a result, even when it costs everything.

In a world that often prizes ease and acceptance, Wroth challenges all Christians and ministers, that faithfulness to God may cost everything, but it is worth infinitely more than worldly approval.

[1] Trevor Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, (The

Congregational History Magazine, Vol.2. No. 5., 1989), 55.

[2] R. Tudur Jones, Hanes Annibynwyr Cymru, (Abertawe: Undeb Yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg,

1966), 42.

[3] Ibid., 57.

[4] W. J. Gruffydd, Coffa Morgan Llwyd (ed. John W. Jones; Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer,

1952), 16-17.

[5] R. Tudur Jones, Hanes Annibynwyr Cymru, 38.

[6] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 9-12.

[7] R. Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’: The beginnings of Puritan Nonconformity in

Wales, No, 3., (Bryntirion, Bridgend: Evangelical Library of Wales, 1976), 12-13.

[8] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 44.

[9] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 10-11.

[10] Ibid., 12.

[11] Ibid., 11-12.

[12] Ibid., 16-17.

[13] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 47-48.

[14] Ibid., 50.

[15] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 14.

[16] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 46-47.

[17] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 14.

[18] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 55.

[19] Quoted by: Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 54.

[20] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 15.

[21] J. Morgan Jones, Hanes ac Egwyddirion Annibynwyr Cymru, (Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer), 11.

[22] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 28-29.

Congregational History Magazine, Vol.2. No. 5., 1989), 55.

[2] R. Tudur Jones, Hanes Annibynwyr Cymru, (Abertawe: Undeb Yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg,

1966), 42.

[3] Ibid., 57.

[4] W. J. Gruffydd, Coffa Morgan Llwyd (ed. John W. Jones; Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer,

1952), 16-17.

[5] R. Tudur Jones, Hanes Annibynwyr Cymru, 38.

[6] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 9-12.

[7] R. Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’: The beginnings of Puritan Nonconformity in

Wales, No, 3., (Bryntirion, Bridgend: Evangelical Library of Wales, 1976), 12-13.

[8] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 44.

[9] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 10-11.

[10] Ibid., 12.

[11] Ibid., 11-12.

[12] Ibid., 16-17.

[13] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 47-48.

[14] Ibid., 50.

[15] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 14.

[16] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 46-47.

[17] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 14.

[18] Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 55.

[19] Quoted by: Watts, William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity, 54.

[20] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 15.

[21] J. Morgan Jones, Hanes ac Egwyddirion Annibynwyr Cymru, (Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer), 11.

[22] Geraint Gruffydd, ‘In That Gentile Country…’, 28-29.

SOURCES

Gruffydd, R. Geraint. ‘In That Gentile Country…’: The beginnings of Puritan Nonconformity in

Wales. No, 3., Bryntirion, Bridgend: Evangelical Library of Wales, 1976.

Gruffydd, W. J. Coffa Morgan Llwyd. Edited by John W. Jones. Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer, 1952.

Jones, J. Morgan. Hanes ac Egwyddirion Annibynwyr Cymru. Undeb yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg,

Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer, 1939.

Jones, R. Tudur. Hanes Annibynwyr Cymru. Abertawe: Undeb Yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg, 1966.

Watts, Trevor. William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity. The

Congregational History Magazine, Vol.2. No. 5., 1989.

The Rev. Shem H. Morgan, a former minister of Tabernacle, Llanfaches, wrote a booklet on the history of the church entitled: A History of Tabernacle United Reformed Church, Llanvaches. I obtained a copy of Shem’s booklet directly from the chapel itself. As it is poorly referenced it has not been used as a source for this article. However, it does contain several interesting details that are likely only known by local people. For example, it includes a sketch of the original chapel at Carrow Hill which was drawn by a member of the church. Apparently, as a child, this church member was taken by his grandmother to see the ruins which were demolished during the early twentieth century, and sketched it from memory. The booklet also provides information about what happened to the chapel in the years following Wroth’s death.

Gruffydd, R. Geraint. ‘In That Gentile Country…’: The beginnings of Puritan Nonconformity in

Wales. No, 3., Bryntirion, Bridgend: Evangelical Library of Wales, 1976.

Gruffydd, W. J. Coffa Morgan Llwyd. Edited by John W. Jones. Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer, 1952.

Jones, J. Morgan. Hanes ac Egwyddirion Annibynwyr Cymru. Undeb yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg,

Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer, 1939.

Jones, R. Tudur. Hanes Annibynwyr Cymru. Abertawe: Undeb Yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg, 1966.

Watts, Trevor. William Wroth (1570-1641): Father of Welsh Nonconformity. The

Congregational History Magazine, Vol.2. No. 5., 1989.

The Rev. Shem H. Morgan, a former minister of Tabernacle, Llanfaches, wrote a booklet on the history of the church entitled: A History of Tabernacle United Reformed Church, Llanvaches. I obtained a copy of Shem’s booklet directly from the chapel itself. As it is poorly referenced it has not been used as a source for this article. However, it does contain several interesting details that are likely only known by local people. For example, it includes a sketch of the original chapel at Carrow Hill which was drawn by a member of the church. Apparently, as a child, this church member was taken by his grandmother to see the ruins which were demolished during the early twentieth century, and sketched it from memory. The booklet also provides information about what happened to the chapel in the years following Wroth’s death.

Written by: Pastor Gwydion Emlyn

Recent

Pursuing Holiness Without Becoming Legalistic

January 29th, 2026

William Wroth: The Apostle of Wales

January 18th, 2026

The Badge of Busyness: when busyness becomes an idol

January 12th, 2026

WE ARE MOVING

January 10th, 2026

The Mystery of Christ’s Temptation: True God, Truly Tempted

January 5th, 2026

Archive

2026

2025

Categories

no categories

4 Comments

Really enjoyed reading this. A fascinating and informative piece of local (and not so local) church history. Right up my street. Must visit the church and chapel in Llanfaches!

May the Tabernacle Chapel reopen its doors soon under a gospel ministry!

Really great read reminding us of our great spiritual inheritance. The challenges from the lessons at the end are really helpful. Go Gwyds…give us more! Diolch yn fawr

Who would have thought there was such a tremendous history to that little chapel. William was a brave soul, was it a hill to die on? maybe, but many worse things are happening in lots of churches now and the Word is picked and chosen to suit wokees, but the mark of the beast has been with us since Pentecost, little marks or big marks and I pray none of us will take it. Keep up the good work, we need to hear it.